A few weeks ago, I was shooting with a friend who owns a pair of Boss side-by-sides. On one target, the clay appeared, he pulled the trigger, and nothing happened. He made

some adjustments and shot. A few targets later, the same thing occurred.

Wondering what could be the matter with his Boss, I raised my eyebrows and he told me that when he closed the gun, the top lever had not come over far enough to allow the safety to be pushed fully forward, hence it was still on “safe.”

“I always hold the lever over when I close the gun, then push the lever back by hand,” he said. “Michael McIntosh said more guns are ruined by closing them and allowing the lever to snap back than any other way.”

It was not just McIntosh. More than one authority has insisted that guns should be eased shut, and the lever then carefully pushed back into position, rather than closing them and allowing the lever to come back under its own spring pressure. This doctrine has spread, and it now seems that if you close a gun normally—that is, properly—you will be accused of vandalism, or worse.

Right off the bat, one should point out that, true enough, slamming a gun shut is not good for it. But between slamming it shut, and closing it like your lover’s door, there is a wide range of practice that is not only acceptable, it’s the way the gun was designed and built to work. In a few cases, the gun will only function properly if you close the gun smartly.

My Charles Lancaster gun is of the famous “wrist-breaker” (self-opening) design, patented by Frederick Beesley in 1884, four years after the more famous design he sold to Purdey.

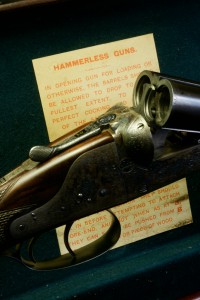

The Lancaster case has several labels, including instructions on how to dismantle the gun and operate it properly. One of the instructions is that, when opened, the barrels should be allowed to drop to their full open position without any hindrance, and the gun should also be smartly snapped shut. With the wrist-breaker, as with any self-opener, there is a definite knack to doing this which becomes effortless second nature but which, I hasten to add, does not in any way constitute slamming it shut.

In the case of the Lancaster, Beesley had refined his principles of shotgun operation considerably, and the design is ingeniously simple. Many functions were performed by just one part—the single-leaf mainspring. Shooting, opening, and closing the gun involve interactions of different parts of the mechanism; prevent one action from functioning fully and you may interfere with the others working properly.

To understand how all this ties together, we need to go back about 130 years to the beginnings of hammerless actions, which occurred coincidentally with the increasing popularity of driven-bird shooting in Britain, and the search for guns which could be loaded and shot quickly.

The first break-action guns required several manual operations to open and close them. They were usually bolted closed with some sort of underlever, of which the Jones, which swings out to the side, is the most familiar. Patented by Henry Jones in 1859, it remained in regular use for more than 50 years because of its strength and dependability.

For driven shooting, however, especially with loaders and pairs of guns, shooters wanted something faster. So gunmakers pursued the goal of the “snap” action—a mechanism that would bolt itself shut automatically when the barrels were closed.

In 1863, James Purdey patented the double under-bolt, which has become the world standard for double guns. This is a bolt in the bar of the action which slides forward to engage two slots in the underlugs. It is usually paired with the Scott spindle, connected to a top lever, but it can be operated with either a snap underlever or a sidelever.

The point is, the under-bolt is drawn back against spring pressure, and that spring then pushes against the under-bolt to snap it into place when the barrels are closed. You will notice my repeated use of the word “snap.” That is the English term for any action that locks shut under its own power, and is both descriptive and evocative.

With speed of loading of the essence, gunmakers refined their designs to make as many operations automatic as possible. The automatic safety grew from this. As the top lever is rotated to the side, a cam on the spindle pushes the safety back into “locked” position.

Obviously, if the lever does not then return completely to its central position, the camming surface will prevent the safety being pushed all the way forward when the time comes to shoot.

This is what was happening with my friend and his Boss.

To return to my Lancaster, when the top lever is moved to the side, the mainsprings push up against the barrels; as the barrels open, the mainsprings cock the tumblers. When the gun is snapped shut, pressure applied to the mainsprings gives them the tension necessary to power the tumblers forward, while another spring snaps the under-bolt closed and a third returns the top lever to its closed position.

As Lancaster pointed out in the case label, it all works perfectly if it is allowed to do so. The shooter just needs to stand back and let the gun do its work without hindrance.

Keep in mind, these guns were built for use in driven shooting with loaders. With birds in the air and guns being fired and passed back and forth as quickly as possible, the guns were snapped shut smartly. They needed to be. They were not eased shut, nor were the levers gently pushed back into position. Woe betide a loader who tried any such thing.

Having said all this, there are millions of double guns in use that are not English best guns, and may require all the help they can get. There are also new guns, especially machine-made guns from Italy, whose bolts and levers are so sticky they need to be manually pushed into position unless the gun really is slammed shut. There is not much one can say about such devices except to hope the owner can soon afford to move up to something better.

Beesley’s self-opening concept was soon followed by others, using a variety of different approaches. Regardless of which principle is followed—whether it is integral with the action, as with the Purdey and Lancaster, or a separate mechanism in the forend, as with Holland & Holland—the self-opener proved itself to have virtues beyond speed and ease of operation.

A self-opener is under constant tension: It is held closed by the bolts, yet it wants to open because of tension from the springs. When the gun is fired, therefore, there is no play in the action. With no play, everything is held tightly at the time of firing, which helps prevent the action becoming loose. This accounts in large part for the legendary durability of the Purdey.

One should add, too, that another vital function—ejectors—depends on the barrels falling smartly, unhindered by the helpful hands of an overly solicitous owner seeking to ease their pain.

To return to my friend and his Boss, I asked if I could look at it, and he agreed. I took the gun, opened it, and then closed it gently but without holding the lever over. No matter how softly I closed the gun that way, the lever was so perfectly fitted that the spring snapped it back into place, dead center of the top strap.

That is the way Boss & Co. intended the gun to be used, and finished it so that it would work perfectly every time. Closed with the lever held over, however, there was just enough friction to keep the lever from springing back into place on its own.

I might point out, too, that the top lever and spindle are designed to pull the under-bolt back, not to push it forward. Pushing it forward that way puts stresses and strains on parts they were never intended to withstand. Minor, perhaps, but worth considering.

And if there is a spring behind the under-bolt, why is it there if not to push the under-bolt forward? We can all become too precious in our approach to good guns. They were built to be used hard yet last forever. Why own a thoroughbred, if you won’t let it run?

To read more great stories like this one go to www.thecontemporarywingshooter.com